Pitchers adjusted their plans for Minnesota’s plate discipline savant and sent him spiraling into a deep sophomore slump. How can he counter and get back into the Twins’ plans?

There are a few different reasons young players experience the dreaded sophomore slump. Sometimes, it’s simply a matter of perception driven by a “failure” to reach elevated expectations after an exciting rookie season. Sometimes, the league figures out how to exploit the player’s weaknesses. Sometimes, it’s simply a regression to the mean after a fortunate start to a career.

Whatever the potential causes, it’s inarguable that Edouard Julien’s 2024 sophomore season was the stuff of nightmares.

His stellar 2023 rookie campaign produced a .263/.381/.459 line that provided a 135 wRC+ mark, but Julien slumped to .199/.292/.323 and 80 wRC+ last season. He was demoted to AAA St. Paul multiple times, and his standing on the depth chart has significantly deteriorated.

After starting last season as the Twins’ second baseman and lead-off man against right-handed pitching, Julien enters the 2025 Spring Training fighting with several others to make the Opening Day roster.

Julien’s path to playing time and potential redemption in year three will hinge on his ability to counter how the league’s pitchers changed their attack plans against him.

Sophomore Slump

As a rookie, Julien’s combination of patience, selectivity, and thump cut the profile of a prototypical modern lead-off man. He walked in 15.7% of his plate appearances while also cracking 16 homers and 17 more extra-base hits in about two-thirds of a full season of playing time.

His plate discipline was among the best in baseball, and he displayed a rare ability to differentiate pitches he could damage from those he couldn’t. That he struck out in 31.4% of his plate appearances and that a lot of those (45.6%) were of the looking variety were pretty much the only complaints we could offer for his work at the plate.

Under the surface, though, there were a few indicators that Julien’s rookie results were somewhat better than he deserved. He outperformed his expected batting average by 30 points, his expected slugging percentage by 32 points, and his expected weighted on-base average (xwOBA) by 21 points. Behind those differences was a .371 batting average on balls in play (BABIP), which was the 5th-highest in MLB.

Still, those marks only portended some regression, not the precipitous fall that came to pass.

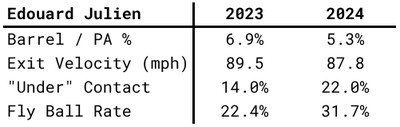

Last season, Julien’s walk rate dropped to 11.0% (still very good, but down 4.7 points), and his strikeout rate ticked up further to 33.9% (46.1% of those looking). The quality of his contact also dipped significantly:

Data from Baseball Savant

He barreled up fewer pitches, didn’t hit them as hard, and made contact “underneath” much more often. His average fly ball traveled 16 fewer feet than as a rookie. The net result was more lazy fly balls that landed in gloves instead of going for extra bases, which played a large role in his BABIP falling 83 points to .288.

Those changed results were a product of how Julien’s swing works and how opposing pitchers adapted their plan of attack against him.

A Game of Adjustments

As we receive new bat tracking data from Statcast and learn to decipher it, we’re becoming smarter about the angle of hitters’ swings and their skill at manipulating the bat to get it to pitches all around the strike zone.

FanGraphs’ Esteban Rivera showed early last season that the angle of Julien’s swing is one of the steepest in the majors.

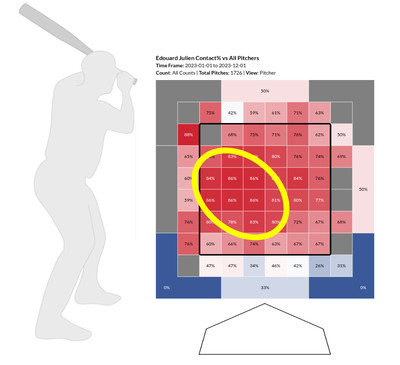

There are some illustrative video snippets of this in that link, and we can also see how his swing path plays out in this FanGraphs heatmap of his 2023 contact rates in different parts of the zone:

Heatmap from FanGraphs

I’ve annotated the plot to circle the locations where Julien made the most consistent contact as a rookie. That yellow oval is angled at about 40 degrees, which matches the average vertical angle of his swings that season. You can probably visualize his swing coming through the middle of that circled area.

A “steep” bat path like this is not necessarily good or bad. Some truly excellent all-around hitters, like Freddie Freeman and Luis Arráez, have steep swings.

Something we’re learning, though, is that steep swings can leave a hitter vulnerable to certain locations and to pitch types that move in opposite ways to this path unless the hitter is highly skilled at manipulating their mechanics to cover other parts of the zone.

Freeman and Arráez are adept at this, which is why they are some of the best contact hitters in the sport. Julien, by contrast, is not as proficient at doing that. His swing path allows him to handle horizontal movement and east-west located pitches well, but vertical movement and north-south locations can give him trouble. That means he can be vulnerable to well-located fastballs up and (especially) to breaking pitches that break underneath his swing.

Fastball Locations

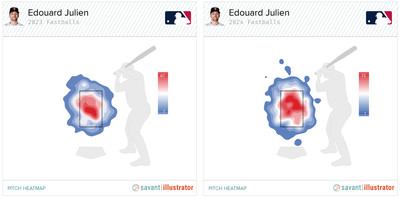

This was evident as a rookie. Julien faced 54.4% fastballs and produced a .405 wOBA and +10 batter run value against them. Davy Andrews noted at FanGraphs that opposing pitchers approached Julien more carefully with fastballs in year two, throwing him fewer (50.1%) and targeting them in more precise locations.

The share of the fastballs Julien faced that were located on the edges of the zone went from 42.9% to 48.0%, and more of them in year two were targeted up and in above his usual swing path, as you can see in these heatmaps:

Heatmaps from Baseball Savant

While fastballs remained Julien’s most productive pitch type group last season, his wOBA on them dropped 65 points to .340.

The average exit velocity on the fastballs he put in play fell from 90.7 mph to 88.7 mph. The launch angle of batted balls is highly correlated with pitch height, and Julien put these more elevated fastballs in play last season at a higher average angle (13°, up from 9°).

This, combined with the reduced exit velocity, helps explain his decreased fly ball distance and BABIP drop.

More Spin

In addition, a fraction of the fastballs he saw as a rookie were replaced by breaking pitches in year two. As a rookie, he faced spin 28.7% of the time and produced a less impressive .303 wOBA and +1 run against them. That’s not bad work in a vacuum, but it was a weakness relative to his work against fastballs. He also whiffed on 43.6% of his swings against breakers, more than double his whiff rate against fastballs.

Naturally, pitchers responded to this by increasing the share of breaking pitches they threw him to 33.4% last season. They were rewarded for that shift when he produced just .194 wOBA and -6 runs while whiffing on 41.3% of his swings against breaking balls.

Pitching “backward”

Opponents changed the what and where against Julien but also the when, which turned his superpower against him.

As a rookie, Julien paced the majors in not swinging at pitches out of the zone. His overall swing rate was the fourth-lowest, and he seemed uniquely capable of laying off pitchers’ pitches.

Opponents discovered that the antidote to that patient discernment was to throw Julien more strikes, especially with their breaking balls in high-leverage counts.

They increased their percentage of pitches in the zone from 49.7% to 50.4%. That doesn’t seem like a meaningful increase, but it nonetheless forced him to see more pitches while behind in the ball-strike count (27.8% of pitches, up from 26.0%), which we know empirically affects batter production.

That production swings most on the results of pitches in even counts. That’s why pitchers have been endlessly coached since Little League about the importance of throwing first-pitch strikes. The difference between jumping ahead 0-1 and falling behind 1-0 is about 90 points of wOBA. Similarly, 1-1 counts that go to 1-2 suppress production by about 130 points of wOBA compared to those that go to 2-1.

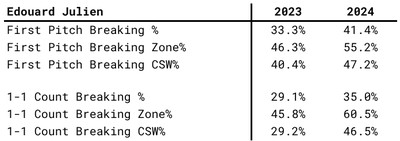

These are the counts where opposing pitchers found a strategy to wrestle control away from Julien last season. They ramped up their usage of breaking balls on first pitches and in 1-1 counts and threw these breakers in the zone more often:

Data from Baseball Savant

Julien, ever disciplined and looking for pitches he could drive, took many of them for called strikes or whiffed to fall behind in the count, making a reality what has been a concern about his approach since his prospect days in the low minors.

Shorting the Circuit

Taken together, these adjustments — more difficult fastball locations, more breaking balls, more count disadvantages — combined with Julien’s passivity at the plate to cause his swing-take decision-making to short-circuit.

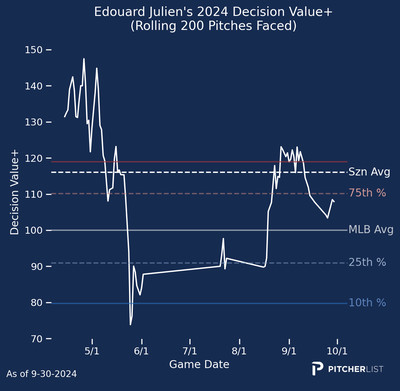

Refraining from swinging at bad pitches is only part of the hitter’s equation. They also need to pick out pitches to hit. Here, the eye test and the data, as measured with stats like Decision Value, agree that Julien lost his balance between the two in the first half of last season:

The deep decline on the left-hand side of this plot shows a hitter who was mixed up, taking pitches he could hit and swinging at pitches he couldn’t. That, as much as anything, drove the Twins to send Julien to St. Paul for a reset.

Punching Back

Julien spent most of June and July with St. Paul, aside from a five-game stint with the Twins in late July, when he struck out in 8 of 15 plate appearances. He returned to the majors on August 16 and received regular playing time for the remainder of the season.

He also returned with a more aggressive approach.

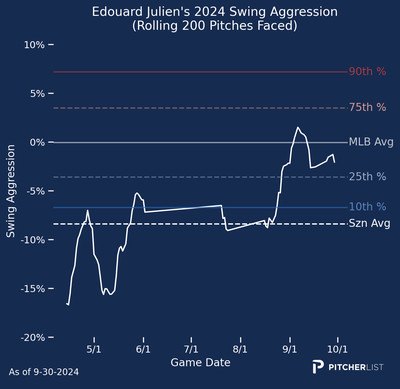

Through July, Julien had swung at only 36.8% of the major league pitches he was thrown and at 56.1% of those in the strike zone. From mid-August through the end of the season, he offered at 49.2% of all pitches and 70.2% of strikes. That adjustment took him from one of the most passive hitters in baseball to nearly league average in terms of swing aggression:

That aggression extended to those crucial ball-strike counts — he swung at 41.6% of first pitches (up from 27.6%) and 59% in 1-1 counts (up from 33.3%).

This adjustment helped Julien rediscover a better balance in his swing-take decisions during the last few weeks of the season, which you can see if you peek back at the right-hand side of the decision value chart shown previously.

Work to be Done

I wish I could tell you that this change fixed everything. But you know it did not.

He hit just .188/.250/.259 in 92 plate appearances over the season’s final six weeks, which was good for a .231 wOBA and a 47 wRC+. The extra swing aggression only modestly reduced his strikeout rate to 30.4%, but nearly halved his walk rate down to 6.5%. It did nothing to improve the quality of his contact nor help him better handle breaking pitches (.205 wOBA, 51.2% whiff rate).

While the results weren’t there, that stretch at least showed that Julien was willing to try to adjust his approach to what opposing pitchers were doing to him. Next might be some adjustments to his swing to give him a better chance on breaking balls and elevated fastballs, which is something that other hitters, like Trevor Larnach and Brent Rooker, have had some success with.

Photo by Adam Bettcher/Getty Images

For his part, Julien seems hopeful he’s addressed that in his offseason work.

He recently spoke with the Twins beat reporters, including Betsy Helfand, and said, “At the end of the year last year, I think my swing was a little messed up. I wasn’t able to adjust to certain pitches and I wasn’t able to hit stuff early, in front, and that’s what I worked on (for) the most part, just to be more through the zone and longer through the zone.”

Julien went on to suggest that the work he did before last season to try to better handle left-handed pitching had a deleterious effect on his swing against righties. He said, “I was more rotated just to be able to face lefties. … It wasn’t a good combo. This year I just focused on the righty angle, righty curveball, righty sliders, so I feel good and I’m sure it’s going to help me against lefties, too.”

Time will tell if he’s right. It’s still very early in camp, and Julien is competing with several others, including top prospect Brooks Lee, for the primary second base job. If he’s going to succeed, showing that he’s again comfortable in his approach and able to handle the adjustments the league has made to him will be major reasons why.

John writes for Twinkie Town, Twins Daily, and Pitcher List with an emphasis on analysis. He is a lifelong Twins fan and former college pitcher.