Going into the 2024 offseason, Brian Flores had a problem to solve. In his first year as the Minnesota Vikings’ defensive coordinator, he had taken a bunch of sub-par talent and run a novel, aggressive defense to strong results, even having a stretch from Weeks 8 to 14 where the team ranked second in defensive DVOA. However, the wheels fell off over the final four weeks of the season. For a team that peaked at sixth in defensive DVOA after Week 14, they fell to 11th by the end of the season. Teams had figured out how to block Minnesota’s pressures and found holes they could exploit the coverages.

In their dominant six-game stretch, the Vikings had beaten up on bad quarterbacks, including Aidan O’Connell, Justin Fields, Russell Wilson, Derek Carr/Jameis Winston, Taylor Heinicke, and Jordan Love before his late-season breakout. Once better offenses and opponents got a bead on them, they allowed 30 points per game over the last four weeks of the season.

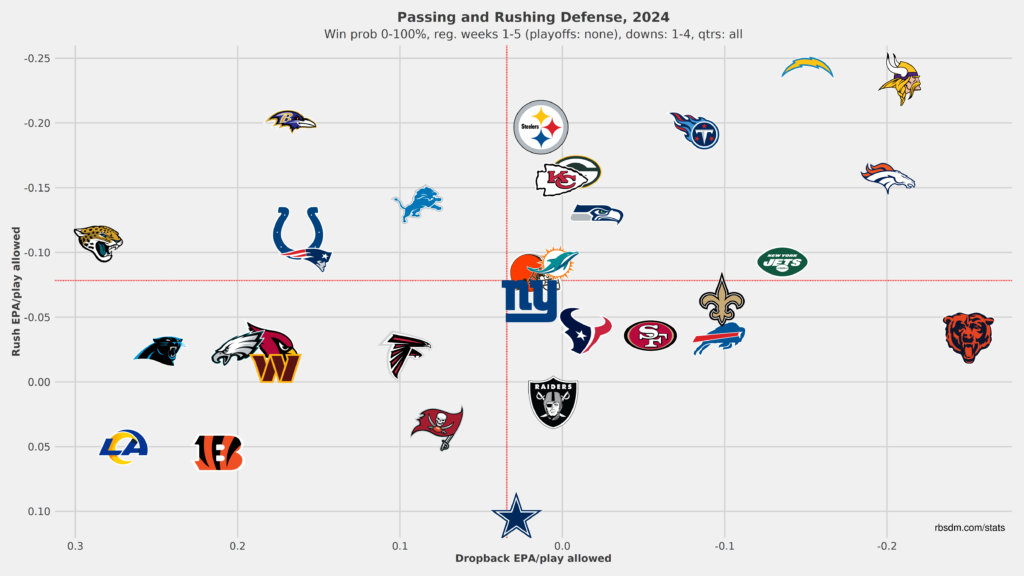

The NFL is an adapt-or-die league, and Flores needed to adapt his defense because Minnesota’s opponents had solved it. Through five weeks, it’s clear that Flores and the Vikings have evolved. They went from beating up on the QBs above to beating up on the game’s best, including C.J. Stroud, Aaron Rodgers, Love, and Brock Purdy — and I guess you can throw Daniel Jones in for good measure. They are the best defense in the league by DVOA and EPA/play, and they’re top two in EPA/play against both the run and the pass.

Kwesi Adofo-Mensah deserves quite a bit of credit, as the Vikings underwent significant personnel turnover this last offseason. They lost a stud edge rusher in Danielle Hunter, as well as role players like D.J. Wonnum, Jordan Hicks, Marcus Davenport, and Mekhi Blackmon (due to injury). However, they added a plethora of talent in response, including Jonathan Greenard, Andrew Van Ginkel, Blake Cashman, Stephon Gilmore, Shaquill Griffin, and Jerry Tillery. Those players have all played 45% of the snaps or more, and all are playing well. The team also added rotational players Jihad Ward and Kamu Grugier-Hill, who are making positive impacts, and first-round pick Dallas Turner is flashing his talent while waiting in the wings.

Talent and scheme have combined to create Minnesota’s great defensive performance, which has led to their dominant 5-0 record. Let’s dive into the tape to see how the marriage between the two has flourished this year.

A baseline of coverage versatility

Last year, the Vikings became known for their aggressive blitz philosophy, the zone coverages they disguised and implemented behind those blitzes, and their willingness to drop out into max coverages. They were a “binary” defense, either blitzing six-plus players or dropping eight into coverage on most snaps.

The Vikings would show very aggressive fronts initially and then drop into safe coverages, which was pretty radical. Disguising coverages and simulated pressures (where a defense lines up several blitz threats on the line of scrimmage but only sends four or fewer rushers) have become popular since the Seattle Seahawks’ style of Cover 3 got phased out of the league by the Vic Fangio defenses. Still, the extent to which the Vikings did it last year was extreme. Fire-zone blitzes have existed for a long time, but it was also incredibly rare for defenses to send six-plus rushers and play zone behind it like the Vikings did. Wink Martindale, the NFL’s other extremely aggressive DC last year, played mostly man behind his six-plus player blitzes.

The difference between Minnesota’s pre-snap presentation and their post-snap coverage is often jarring. The play below is Cover 3, with Josh Metellus, the deep third player, on the line of scrimmage at the snap:

The Vikings also used a similar structure to get to Quarters:

They love to play with three players deep pre-snap. Often, it’s Tampa 2 or Cover 3. However, this year, they’ve also run Cover 1 out of it:

Think it’s an all-out blitz? Nope, how about two deep safeties instead:

Finally, here’s a bunch of ways the Vikings got to Tampa 2, one of their favorite coverages:

That’s an unreal amount of movement for the QB to decipher post-snap, making it difficult to determine what throw is coming when dealing with a pass rush.

A limited coverage menu in 2023

The novel scheme confounded offenses, but it had a problem. When the Vikings dropped out of their blitz looks, they only ran two coverages: Tampa 2 and Cover 3. Once teams, starting with the Cincinnati Bengals, figured this out, they were able to spam plays that attacked the middle of the field, like Dagger. Minnesota’s three- and four-man rushes, lacking juice beyond Hunter, couldn’t get home, and quarterbacks were able to diagnose the defense despite the post-snap movement.

Below is an example against the Bengals. The Vikings drop out into Cover 3 (note Harrison Smith and the outside corners dropping deep), and the Bengals concept attacks a void over the middle (and Ivan Pace) in coverage:

Here’s a Tampa 2 look (note Smith in the middle with more depth than the LBs, but shallower than the two deep players in Byron Murphy and Camryn Bynum) that the Bengals attacked well but could not connect on:

You can see the common theme of Tampa 2 and Cover 3 on a number of the successful plays against the Vikings from the end of last year:

The numbers backed up the anecdotal evidence that the Vikings ran a lot of Tampa 2 and Cover 3. Like most NFL teams, they were primarily a Cover 3 defense, running it 36% of the time. They also ran by far the most Cover 2 (most of Minnesota’s Cover 2 snaps were Tampa 2) in the league last year, at 28%, and also ran by far the most Cover 0, at 11%.

personnel improvements lead to more variety in 2024

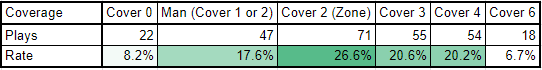

This year, I’ve begun my own charting of the Vikings’ coverages. I’ve charted all 268 coverage reps the Vikings have run (including sacks, scrambles, and plays negated by penalty), and they’ve become more varied in their coverages. They now run man coverage (either Cover 1 or 2 Man), Cover 2, Cover 3, and Quarters at roughly equal rates, ranging from 17-27%.

In my opinion, the Vikings ran so little Man and Quarters last year because they had no faith in their outside CB situation. Murphy played great for most of the season, but the defense fell apart once he went down, and young players Akayleb Evans, Andrew Booth, and Mekhi Blackmon struggled to play consistently. In bringing in Gilmore and Griffin, the Vikings traded Booth and relegated Evans to the bench, while Blackmon unfortunately suffered a season-ending injury in training camp.

Griffin has made a Pro Bowl, and Stephon Gilmore is a former Defensive Player of the Year. They may not be at their athletic peaks, but they are sound players you can trust one-on-one on the outside in coverage. Man coverage is obviously difficult for any CB, but both have the chops to pull it off. Quarters stresses CBs because you often have to play MOD (man outside or deep), where you need to take deep or shallow routes to the outside with no underneath help. In Cover 3, you only have to worry about your deep responsibility, with help underneath. In Cover 2, you only have a flat responsibility with deep help.

Here’s a great example of Gilmore playing Quarters from off coverage. You can’t let your opponent run by you, so it takes a nuanced understanding of routes to protect against the deep ball while remaining in position to drive on routes that break short. In the play below, Gilmore toes this line well and can break on the curl route to get a pass breakup at the top of the screen:

Zone coverages are great, but man coverage is also necessary for high-level defenses. On third downs and in the red zone, there are situations where you will have to line up one-on-one against your opponent and outplay them. Gilmore and Griffin give the Vikings the capacity to do that. In the play below, Griffin mans up against Brandon Aiyuk, the top receiver of the bunch, Gilmore takes Deebo Samuel, the bottom receiver, and Murphy takes Jauan Jennings, the point man of the bunch. All three corners lock their receivers down. That’s not something the Vikings could rely on last year, and it’s why they ran man on only 8% of their snaps.

Outside of Minnesota’s CB room, their safety trio of Smith, Bynum, and Metellus has continued to play at a high level. But the addition of Cashman has been a revelation. His coverage instincts and range have transformed the Vikings’ coverages. For as good as Pace is going forward, he struggled on a number of coverage plays last year, and that helped leave the middle of the field open on a regular basis. Cashman has closed it. Look at the play above or the one below where the Vikings are in Quarters. Quarters helps prevent deep throws but leaves a lot of space available underneath for passers to check down.

They only way to close those windows is with speed and elite coverage instincts, and Cashman has them:

Minnesota’s defense hasn’t been impenetrable. Well-placed seam balls against Tampa 2 have been effective, as well as in-breakers against Cover 3 paired with play action to suck up the LBs. Throws to the flat have been an issue against some Quarters looks. Malik Nabers got a big play against Gilmore’s man coverage in Week 1.

These weaknesses aren’t unique to the Vikings; they’re struggles that every team experiences in those coverages. Last year’s defense struggled at the end because they got predictable and couldn’t rush the passer effectively. They were predictable because they didn’t feel comfortable expanding their coverage menu. This year, they acquired better personnel. On the back end, that’s allowed them to run a wider variety of coverages, making them difficult to decipher. On the line, that’s put opposing QBs under more pressure, limiting the time they have to sit back and pick apart zones.

further schematic tweaks based on personnel

Because the Vikings have better players, they’ve also been able to make a few tweaks to tune-up the scheme and create tighter coverage windows.

First, they’ve tightened up the way they’ve played their Tampa 2 zones. They’ve been responding much better against Dagger, a concept they struggled against last year, along with other plays with dig routes. The deep safety will cover the vertical route, and the Tampa player will undercut the dig. That’s exactly what happened on this Grugier-Hill interception:

The improved play has made it difficult to attack the middle of the field against this team. You have to rely on in-play adjustments to beat the quality coverage the Vikings are playing. In the play below, Stroud wants to hit the dig route by Nico Collins underneath a vertical route. However, Cashman is expertly patrolling the middle of the field, so Stroud makes the choice to throw the ball behind Collins to create space that isn’t there. Collins isn’t on the same page, and the ball goes to Bynum for the INT.

In the below play, you can see a mixup from last year. The high hole player gets sucked up by the seam route, leaving the dig wide open. This contrasts well with the play above, where Cashman was able to get underneath the area where the dig was:

Flores’s next tweak is to his infamous Cover 0 “Hawk” blitz. Here’s a full explanation of the blitz. However, the critical component that Flores changed was how the players on tag pressures — the ones who initially step forward to blitz but then fall off into coverage — operate in coverage.

Last season, there were many situations where the blitzers didn’t drop back into coverage at all, like the play below:

In other cases, Flores had a player drop, but the rule appeared to be to angle your drop away from the slide of the offensive line. Theoretically, that makes sense. The blitz guarantees an unblocked rusher, and if the offensive line is sliding to your side, the unblocked rusher is coming from the other side.

Usually, hot routes are designed so that when a QB and receiver recognize an unblocked blitzer, they run a hot route to “replace” the space that the blitzer vacated. In theory, teams will often respond by trying to throw hot to the side they slide away from, so you should angle your drop that way.

However, offenses got wise to what the Vikings were doing. They started to slide towards the side, where they had multiple players in the passing concept, and then they ran route concepts that quickly got receivers open through rub or pick routes. The QB would then be responsible for getting the ball out before being hit from behind. The play below is a good example, where the Los Angeles Chargers run a vertical route as a pick for the slant underneath. You see Jones, the tag player, drop the opposite direction, and Justin Herbert quickly gets the throw out, away from his drop.

This year, the Vikings updated how they make that drop. They still drop the player who is getting slid toward, but they have him read the eyes of the QB instead of immediately angling his drop toward the slide. It probably also helps that they got a personnel upgrade. Van Ginkel, a player with a lot of experience with Flores from Miami and is a versatile coverage/pass rush player, is now often dropping instead of Jones, a player who had very limited coverage experience in his first year with Flores last season.

The difference is obvious in Van Ginkel’s pick-six against the New York Jets. The Jets are running a similar concept to what the Chargers play, with a vertical route by the TE that’s a blocker and a slant underneath it. New York slides right and leaves Smith unblocked on the back side, but Rodgers gets the throw out before that rush matters. The difference is Van Ginkel, who watches Rodgers’ eyes and drops underneath the throw rather than dropping towards the slide like Jones does above. Thus, he’s right in the path of the pass for an interception.

The Vikings have done excellently when they’ve run Cover 0 so far this season. On 22 reps, they’ve gotten three sacks, forced a backwards pass/fumble, forced another fumble after a completion, and gotten two interceptions, including the pick-six above. They’ve only allowed 11 completions, and only three have gone for more than 10 yards.

Here’s a compilation of their seven Cover 0 reps against the Jets:

Better players have allowed the Vikings to run a wider variety of coverages, and they’ve also enabled them to run those coverages more effectively. Flores is cooking with the great ingredients he’s been given.

improved talent leads to better pass rush

Hunter had a great year last year, with 16.5 sacks, 80 total pressures, and a 25% win rate against true pass sets per PFF. With his departure, it was fair to question whether the Vikings would be able to replace his production.

However, the components outside of Hunter fell far short of what was needed to maintain a quality pass rush. Even though they blitzed over 50% of the time last year, an astounding rate, they were only 21st in pressure rate overall. Per PFF, they ranked just 24th in pass-rush win rate as a team, at 39.9%.

Some of that was due to opponents’ quick passing, but their complementary pieces just weren’t winning when given the opportunity. Wonnum’s 13.8% win rate against true pass sets ranked 73rd of 118 players, and Pat Jones was 71st at 13.9%. It was even worse on the interior. Phillips ranked 99th of 129 qualifying players, and Bullard was 114th.

The Vikings brought in Greenard to replace Hunter, but critically he wasn’t the only move that they made. They also added Van Ginkel and Ward through free agency, as well as Turner through the draft. Retaining Jones allowed the Vikings to have a strong rotation even though Turner is still adjusting to the NFL. Greenard, Van Ginkel, Jones, and Ward rank in the top 62 of pressures, and Greenard is tied for second across the entire league, according to PFF.

On the interior, the Vikings also brought in Jerry Tillery in part due to his pass-rush skills. He has eight pressures and an 8.1% pass rush productivity against True Pass Sets, 39th among interior defenders and far better than what we saw from Phillips and Bullard last year.

The tape matches up with the numbers. Greenard has been particularly dominant, and here’s a compilation of his wins:

In addition, Ward has allowed the Vikings to run an interesting wrinkle. He’s an ideal candidate to rush inside on passing downs because of his frame (6’5″, 285 lbs., with nearly 34″ arms). The Vikings treat him as a DT on those downs, which means they have been able to put four edge rushers on the field.

Ward’s impact has been felt with his ability to get upfield and pressure the QB, as well as set up stunts, like on Turner’s first career sack:

Here’s a play that led to a big hit on Rodgers:

Phillips is a great run-stopper but can’t do nearly what Ward can as a pass rusher. He’s enabled the Vikings to consistently win in passing situations, which they’ve been in a lot this year, given all of their leads.

still dominant run defense

Speaking of stopping the run, the Vikings have still proven great at it. They allowed just 3.8 yards per attempt last year, tied for fourth in the NFL. They’re even better this year, allowing just 3.6 yards per attempt.

Opponents struggle against Minnesota’s run defense for three primary reasons. The first two are schematic. The Vikings often play with single-high structures on early downs and many bodies around the line of scrimmage, filling every gap and making blocking difficult. Second, they run stunts at a high rate. Stunts confuse linemen by changing their blocking angles immediately post-snap.

Here’s a stunt that ended up in a tackle for loss against the Texans:

The third reason is personnel. Phillips and Bullard are technically sound run defenders, consistently controlling opposing blockers and shedding blocks to make the play. Tillery also has had his share of flashes. Minnesota’s edges, particularly Greenard, are strong and evince good technique when setting the edge; they’re fast enough to chase down runs from behind. At LB, Pace is a menace against the run and so quick that he’s virtually unblockable. Cashman can get stuck on blocks, but his speed often allows him to get into the backfield untouched as well. The DBs, particularly Metellus and Smith, also excel doing the dirty work of run defense.

Phillips got an extension from the Vikings because of his excellent run defense and leadership along the front:

Bullard with a great run-defense rep:

Tillery with a great example of a block shed:

Here’s an example of Greenard setting a hard edge and making the tackle:

Van Ginkel also stacks and sheds TEs very well:

Jones has been explosive in the backfield all season and is tied for fifth in the NFL with five sacks. However, it also shows up in the run game:

Turner’s acceleration is an asset in run defense:

Pace simply moves differently from other humans in this compilation of plays against the Jets:

Cashman has great speed to get into the backfield and make plays:

Run defense is a team effort, and Minnesota’s defense makes for a great team. That’s why they’re successful.

defensive resiliency

One of the most impressive parts of this defensive performance is how many plays the Vikings have faced while staying so strong. They’ve maintained the top defense in the NFL despite facing 343 plays, which is the second most in the NFL behind just the Indianapolis Colts. The Colts (352 plays against), Tampa Bay Buccaneers (340), Atlanta Falcons (327), Jacksonville Jaguars (327), and Bengals (327) all rank 20th or worse in defensive EPA/play, while the Vikings are first.

Why have the Vikings allowed so many plays? They’ve had a high number of drives against them. The offense, while efficient, isn’t holding on to the ball for extended periods of time. They only average 5.1 plays per drive, tied for 29th in the NFL, because they either score, punt, or turn it over quickly. That means the Vikings have faced 60 total drives. If you exclude drives that ended at the half or when the clock ran out in the fourth quarter, the Vikings have faced 59 true drives, which is more than any other team. That’s how they’ve allowed so many plays despite ranking average in plays allowed/drive (5.8, tied for 14th) and quite good in yards allowed/drive (26.3, ninth).

It’s also notable that they’ve been playing from ahead for the whole season and with a fair amount of garbage time, with the exception of the Jets game. (On defense, they’ve only taken the field 16 times during games that are within eight points.) Passing is generally more efficient than running, so it’s notable that the Vikings have such a good defense by efficiency metrics and yards/play (where they allow 4.8 yards, tied for fourth) despite facing 230 passing attempts by opponents, which leads the league by 25 over the Bucs and more than 40 over any other defense.

Teams are constantly playing catch-up against the Vikings, who are preventing their opponents from making games close. The Jets are the only team this season to begin a fourth-quarter drive with a chance to tie the game or take the lead against Minnesota this year. They took a sack and went three-and-out on their first opportunity and threw an interception on the second. Door slammed shut.

So is the defense sustainable?

Given what happened last year, it is fair to ask whether Minnesota’s defensive performance is sustainable this time.

The Vikings have forced 13 turnovers this season, tied for first in the NFL. Still, the turnover rate doesn’t feel unsustainable. Minnesota has 11 interceptions to just two fumble recoveries, and fumble luck is much more random. The Vikings have even been on the bad end of fumble luck, as they’ve only recovered two of their opponents’ six fumbles.

Quite a few of Minnesota’s interceptions have come off of tipped passes, but those tips are happening because of good timing by the defensive linemen and tight coverage downfield. The Vikings have 41 pass deflections on defense, 13 more than the Bucs, who are in second. The difference between them and Tampa is the same as the difference between the 28th-place Washington Commanders. There have also been a ton of near misses.

Remember the screen Smith nearly batted to himself against the Texans? Or the batted ball Rodgers nearly caught himself against the Jets? With better luck, either could easily have been intercepted. Opposing QBs have had 12 total turnover-worthy plays passing against the Vikings, so they’ve caught one fewer interception than opponents have gifted them.

Minnesota’s defense feels sustainable regarding performance outside of turnovers. The team is running a strong variety of coverages and gets to them in unique ways. Their coverage players are very sticky. They consistently win as pass rushers. Their run defense has been dominant.

Some opponent may find the key to unlock Minnesota’s coverages, but it’s a lot less likely this year than last due to their increased coverage menu and given that they’ve already faced their best opponents. They have big tests in Jared Goff (with Ben Johnson) and Matthew Stafford (with Sean McVay) coming up. Otherwise, they’ve probably already faced the best QBs they will see all season.

At this point, Brian Flores seems to have built a defense capable of taking on modern offenses and winning.

(@fball_insights)

(@fball_insights)